What EXACTLY is a Pandemic?

What’s the difference between a nasty weekend flu that’s going around and a pandemic? Body count. That’s one way to look at a major catastrophe caused by a rapidly spreading disease. This is not a theoretical subject.

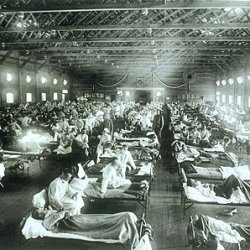

In 1918 an influenza outbreak, variously called the Spanish Flu Pandemic, the 1918 Flu Pandemic, or simply The Great Pandemic, infected about 500 million people in almost every country of the world and killed 50-100 million men, women, and children, 3-5% of the world’s population. Think about that for a moment.

It obviously wasn’t the end of the world. In fact, most people today have little or no knowledge of the 1918 pandemic; even though it happened within memory of people still alive and at a time when modern transportation (except airplanes) and modern medicine already existed.

The Nature of a Pandemic Disease

Pandemics start out as epidemics. Doctors and health authorities spot epidemics when they recognize a pattern of unexpected disease occurrence, where the disease or its frequency is unusual. By loose definition, an epidemic is an outbreak of any disease above expected levels.

An epidemic doesn’t always mean a contagious disease, for example, we use quasi-medical expressions such as “there was an epidemic of car accidents that day,” or “in that city, schizophrenia reached epidemic levels.” In terms of effect, epidemics can be just as deadly as a pandemic.

These days, an epidemic turns into a pandemic under certain conditions that include: spreading to a wider geographic area (neighboring states or countries); the infection is easily transmitted between people and at an unusually high rate; and the type of disease poses a serious health threat including fatalities (as with influenza or un-treatable infection). Most people associate pandemics with potentially a worldwide outbreak.

Most people also associate pandemics with influenza and rapidly spreading diseases. This is accurate as far as it goes, but pandemics also include diseases that spread more slowly, such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and cholera.

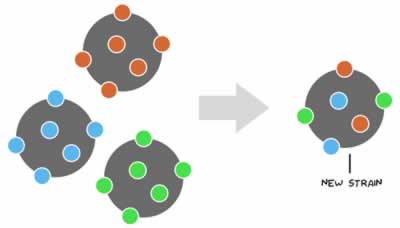

In fact, arguably the main characteristic of modern pandemics is that they represent dangerous mutations, which are variants of well-known diseases.

Because pandemic causing diseases are usually genetic variants, their origin can be difficult to trace. In many cases, the source is animals. With names like swine flu and bird flu these viral infections live in animals, often harmlessly, and then develop a mutated strain that affects humans.

The biochemistry of these strains can be extremely complex, but the subtle variations in genetic and chemical composition often determine the virulence of the disease.

From a survivalist point of view, pandemics are an asymmetric event. People get very sick and often die in a pandemic, but for the most part the infrastructure and physical environment is unharmed. Phones still work, transportation is available and no buildings are destroyed.

Pandemics have yet to produce dramatic collapse of social or economic order (although they could), so preparation for pandemics is mostly a matter of preventative measures.

The Un-treatable Pandemic

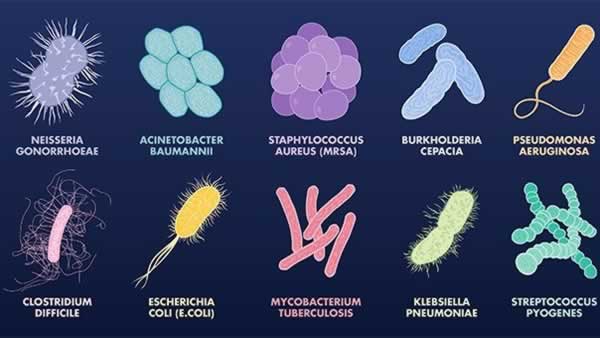

Developing over the last few decades, there is a frightening new potential for pandemics – drug resistant strains of certain diseases. There is so much medical treatment, especially with antibiotics, that many diseases are now mutating to produce strains un-treatable with the usual convenient and inexpensive drugs.

For example, tuberculosis, a disease considered eradicable in 1960, is now staging a comeback in forms that are very difficult and expensive to treat. The nightmare of health authorities is the outbreak of some rapidly spreading disease that is also drug-resistant – an un-treatable pandemic.

The Dispersal of Doom

Calling pandemics “the dispersal of doom” is an over-dramatization, but it highlights something about modern civilization that magnifies the potential for dangerous pandemics. As the mobility of a population increases, so too does the risk of rapidly spreading highly infectious diseases. A great deal of study and research has gone into pandemic dispersal, which could be subtitled “Planes, trains and automobiles.”

Diseases that might once have taken months or years to spread can now disperse in days or even hours – thanks to modern transportation. Air travel in particular makes it possible for diseases to spread from continent to continent very rapidly.

In worst-case scenarios, a viral disease with the right characteristics could infect a sizeable percentage of the world’s population within a week. It’s not hard to understand why this kind of scenario is the subject of many novels and movies. (To name a few: The Andromeda Strain, Outbreak, 28-days Later, I am Legend, Contagion.) There’s no doubt these doomsday accounts of pandemics remain effective because the threat remains real.

The Risk of Pandemics

If you wanted to pick a survivalist topic that would generate the least controversy, it would be pandemics. The threat of pandemic is real, or in a word, chronic. Viruses and other fast spreading diseases are always around, often causing ‘localized’ problems and the occasional panic.

However, the most important point is that at almost any time a weaker virus can mutate into something far more lethal and begin spreading around the world – becoming a pandemic.

Since the first was recorded in 1580, pandemics seem to occur between 10 and 30 years apart. This isn’t a predictable cycle, but it shows that the appearance of virulent diseases is a regular feature in human history – and we can expect to continue that way.

Compared to many potential catastrophes on the survivalist’s list, pandemics and serious local epidemics are the most likely to occur within any person’s lifetime. Many also feel that the risk and severity of pandemics is also increasing with modern traveling lifestyles and the rise of drug-resistant diseases.

Reacting to a Pandemic: How to Survive a Pandemic

Getting accurate information is crucial in almost all survival situations, but none more than in dealing with pandemics. Making an appropriate response to a pandemic is a function of correctly understanding the circumstances – a matter of being well informed. There are many factors involved in the severity of a pandemic, for example:

- Transmission vector (spreading through air, water, food, human physical contact)

- Dispersal rate (how quickly the disease spreads, geographic coverage)

- Diagnosis (name and type of disease)

- Intensity of the disease (infection rate, symptoms and illness cycle, fatality rate)

- Vulnerable populations (old, young, women, men, healthy or unhealthy)

This is information that public health organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and Center for Disease Control (CDC) in the United States, try to acquire as early in an outbreak as possible. It is not always easy to do this, especially for diagnosis. It often takes days before the nature and patterns of an outbreak are known.

In general, you should have an emergency supply of food, water, and other essentials, as well as a fully stocked first aid kit. Extra soap, anti-bacterial wash, and alternate sanitation supplies such as trash bags, toilet paper, and kitty litter should be added to your emergency survival kit.

You won’t be able to make specific preparations or take action until a pandemic (or epidemic) is officially declared and its characteristics mostly understood.

For some types of pandemic, there may be treatments or even vaccines, but they are usually custom made for a specific outbreak, so there is little point in attempting to stockpile all but the most generic medicines (e.g. something like Tamiflu, ibuprofen, medicines you take on a regular basis).

In a similar vein, stockpiling surgical masks or installing biologically effective air filtering systems covers more than pandemics (e.g. bio-terrorism), but many forms of disease do not have an airborne transmission.

Still, having a supply of N95 medical masks means that you can better protect yourself if you have to go out and be exposed to other people. Again, what’s appropriate depends on the type of disease.

Once an outbreak begins, obvious survival tactics apply – avoid areas with people known to be infected (which may boil down to just avoiding people),wash your hands, and cove open cuts/scrapes to help reduce the chances of the pathogen gaining access to your bloodstream.

If a pandemic reaches your geographic area, then generalized BOL (Bug Out Location) strategies – with stockpiled food, water, medicines – may be the best response, provided you’re not bringing the disease with you.

How much a pandemic or serious regional epidemic disrupts employment, finance and social connections depends on the severity and duration of the event. The Spanish Flu Epidemic came in two waves over a period of 24 weeks.

The first wave was more like a ‘typical’ influenza epidemic and lasted about 18 weeks. The second wave, caused by a newly mutated strain, was by far the most lethal yet it died out very abruptly (in about a month in most locations).

In some communities, there were extreme shortages of medicine and particularly medically trained people (many died); other communities suffered negligible or minimal disruption.

Despite tens of millions of dead (about 500,000 to 650,000 in the United States), even the Spanish Flu Pandemic did not cause economic or social chaos. We can hope that a similarly lethal pandemic today would be at least as well contained.

Leave a Reply